Monday

The week began with a visit from researchers from Uware Robotics, who have developed an affordable AUV (Automated Underwater Vehicle) which Mare will test drive today at Quinto do Lorde on the South of the Island. The AUV, which is used for underwater data collection, has a raspberry pi and camera for demonstration purposes but can be equiped with a high res camera or whatever sensors are needed. Direction can be given via an audio transducer from the surface but can also operate automatically for mapping missions. The module is able to stabilise itself, using its four propellors, at a ‘home point’ in the water to which it can then return for collection (within an error margin of two meters over two hours).

I was curious as to whether audio data could also be collected by the AUV, but due to its own engine noise, this would only be when the vehicle is stationary which would defeat th purpose, since this could be accomplished much more cheaply through a stationary PAM (passive acoustic monitoring) device such as Mare already deploy at various sites.

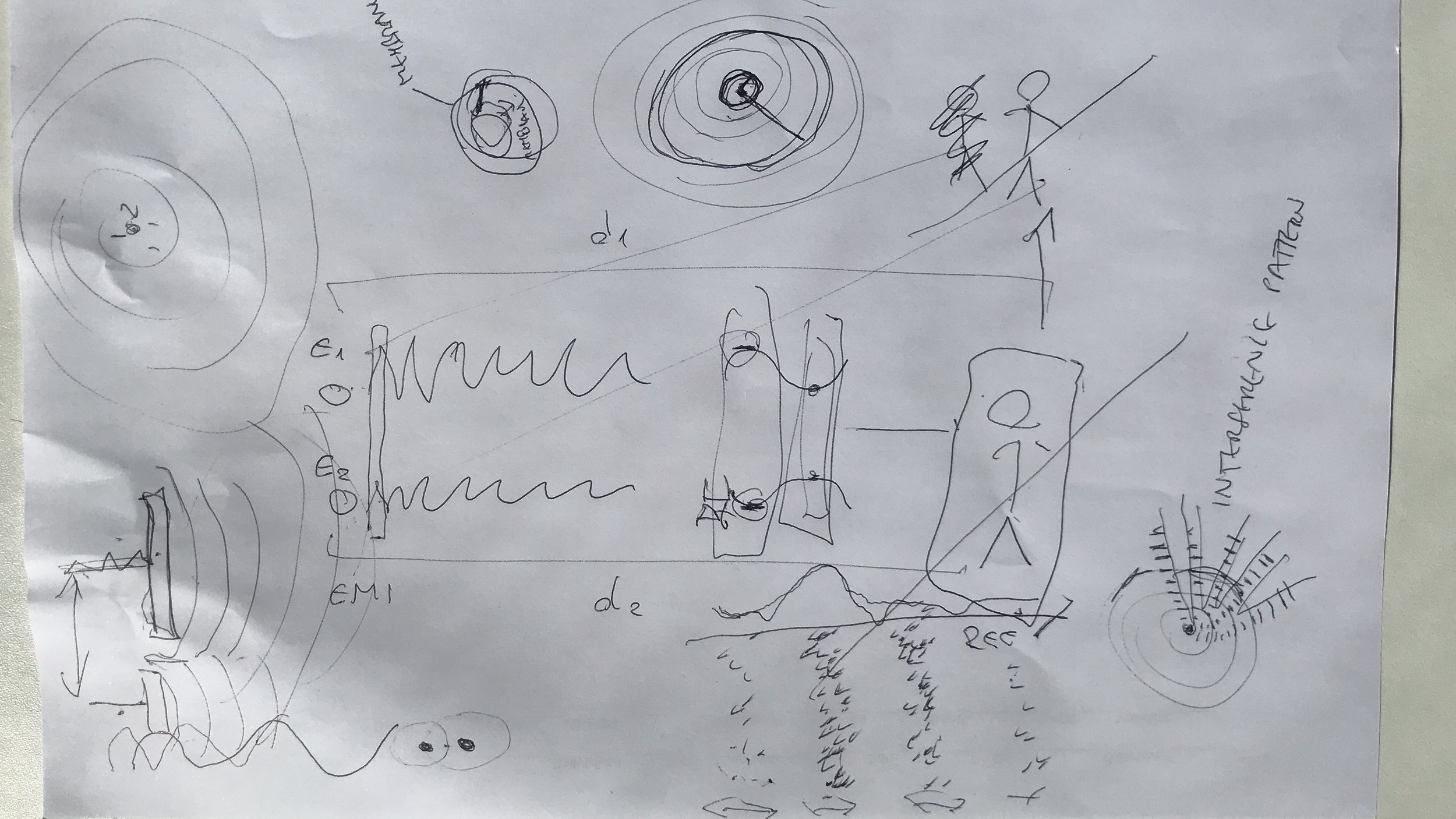

My question led to a discussion between myself, Marko and Francisco (Silva, research technician in Wave Labs) about the theoretical possibilities of noise cancelling at source for an engine. At one point I asked whehter a membrane inside a membrane would ever be feasible. It was concluded it might be theoretically possible, but if it worked it would probably mean the desired motion provided by the engine would also be cancelled. This is a very interesting thought experiment for me, given I’m exploring questions of the links between sound, motion and touch in my research.

Wednesday

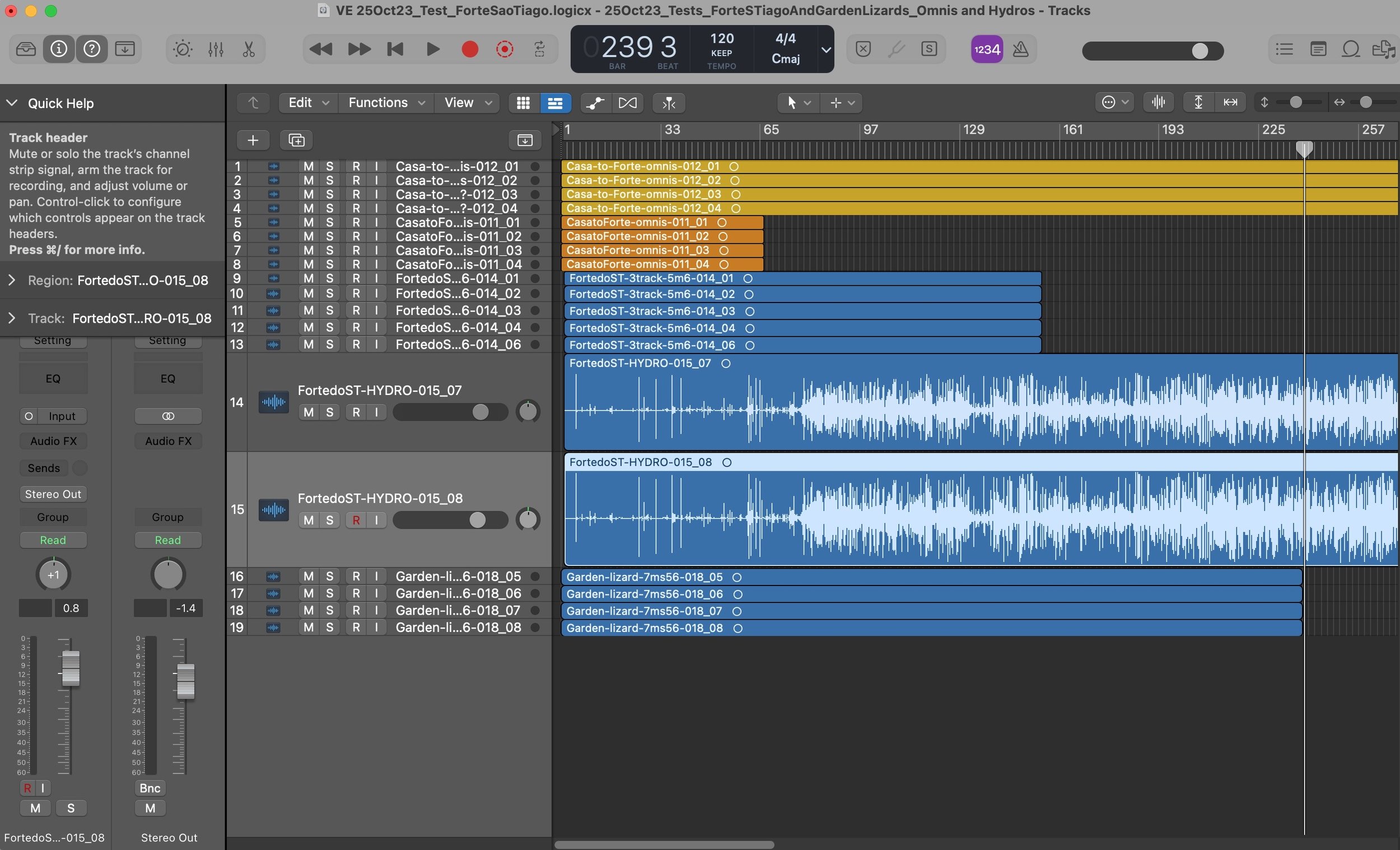

I spent a day out of the office, testing my mix-pre 6II with JrF series hydrophones off the town beach under Forte do Sao Tiago and learning to use the new kit. Used my set of omni directional lavalier mics (Omnis) with their wind shields attached to my headphones, while walking and then introduced the hydrophones at the town beach under Forte do Sao Tiago.

In the afternoon I filmed and recorded lizards some lizard (I presume common wall lizards) who were very active in the yellow guava tree in my small garden.

Notes on how to import - if you drag from finder you can import separate tracks - if not it just uses the pre-mixed file.

Remember you have to select no input (unless you want to record over the file) and output as either mono, stereo or surround.

Not sure yet how to find the details of bit depth and sample rate once it’s imported. Gonna look on recorder and see if it’s stored. Check that any important files have been transferred (and backed up) before deleting from SD card.

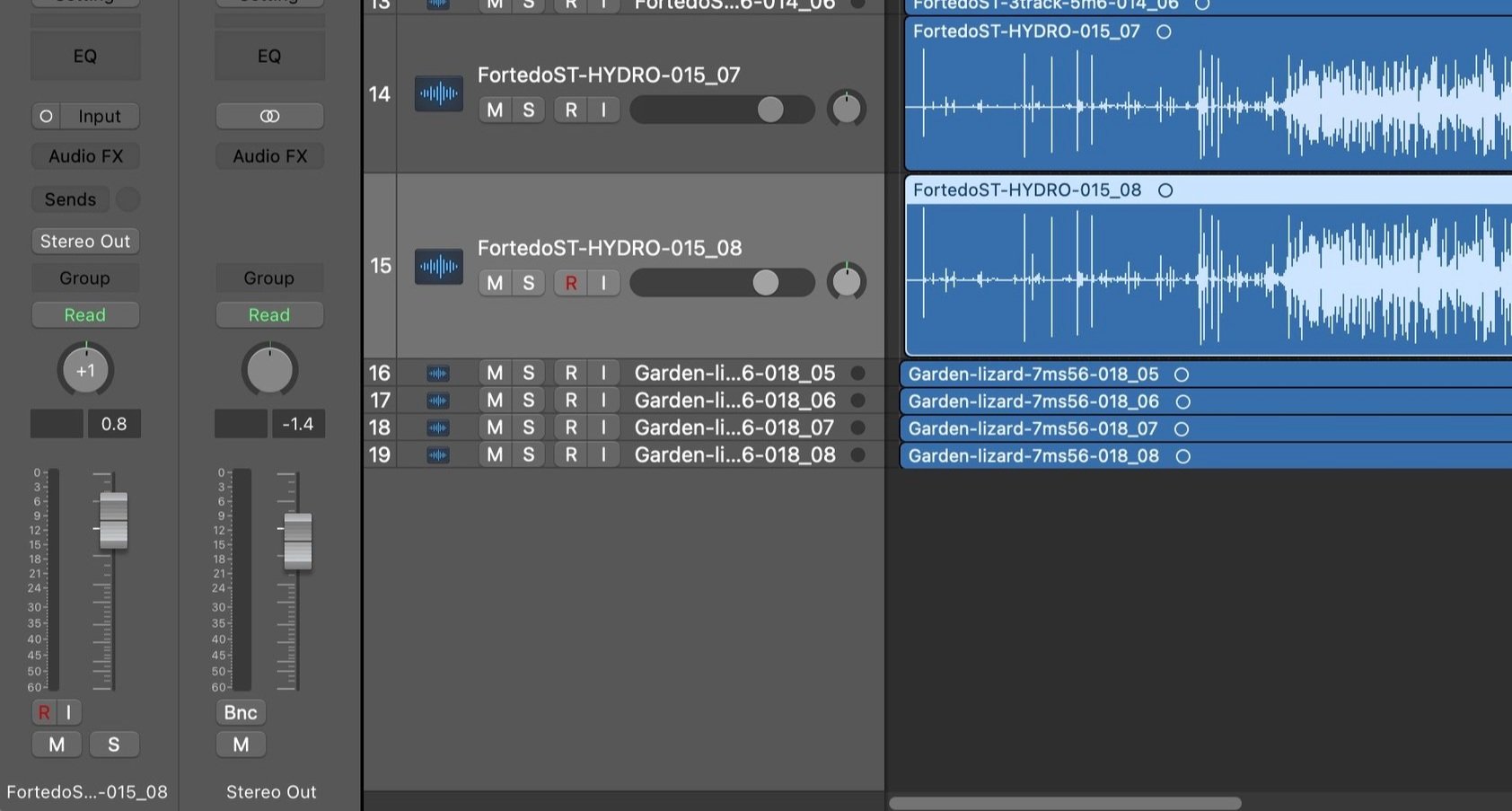

On the Hydro tracks (15) for some reason I picked up an extra track. I think because the other hydrophone was armed, even though it was curled up on the bag and not in water. interesting how sensitive that is, because it also sounded like water, just a lot quieter. JrF ydrophones are basically waterproofed contact mics.

Most of the sound in any case is just a combo of surface swirling and a lot of clicking that I presume is the sound of sand or pebbles rolling around in the distance? There were fish right by my mic, but not idea if they were making any of these sounds.

It’s very obvious where I was dragging the mic or touching the wire, so that’s not possible to confuse with anything else which is good.

On track 015, I think the explanation for why there is suddenly more data is because I may have changed the settings in the middle of things? I don’t know. The same rate shouldn’t really make any difference unless I slow somethign down or speed it up… Oh I know, I maybe upped the gain on that track after realising it was too low. OK I get it.

NB: Lizard recording - was done without wind mufflers which is a shame but you can really hear them scuttling about in the tree which is lovely.

To Do:

need to understand how to edit 35bit float - do I need to do something special?

Also I don’t really have an answer yet to my question about whether it is worth recording in 192sample rate….

Need to experiment with time-stretching to see.

In main menu under record you can change sample rate (a bit like the audio equivalent of frame rate). 192kHZ is a very high frame rate which will make the file larger and more difficult to process, but if slowing down (stretching) the audio to bring higher frequencies into audibility this will mean a high quality can be maintained. Shouldn’t be necessary for lower frequencies which would need speeding up instead. Need to check my reasoning here.

32 bit float allows for lossless processing - useful for either when the gain is set wrong, or you want to record an extremely broad dynamic range.

Need to check whether anything special is needed to edit in this mode.

WHAT CAN WHALES HEAR? LISTENING WITH WHALES

Convo at lunch on Monday 23 Oct, with Alejandro Escánez Pérez, Post-Doctoral Fellow working on taxonomy, systematics and ecology of cephalopods from Macronesia (Madeiran islands and Azores). I asked what the emblematic whale for Madeira was and about the whale with the biggest range of hearing. The sperm whale and pilot whale are both candidates, but baleen whales such as the blue whale have calls that are lower frequency which suggests lower frequency hearing.

Left: Sperm whale - Odontoceti; deep diver so hears to low frequency of about 38hz; associated with Madeira strongly through history of whaling.

Right: Pilot Whale. Odontoceti; deep diver, most frequent visitor to Madeira.

The classification of whales and dolphins is more complicated than I realised. The name whale and dolphin are just common names. They are all cetaceans, and some that belong to the family Delphinidae (what we might think of as dolphins) are commonly called whales (such as killer whale and pilot whale). Some of the well-known ‘whales’ like the sperm whale, are classified along with delphinadae as odontoceti (toothed whales) and therefore can be thought of as closer to the dolphins than their other whale cousins the mysteciti (baleen whales) in terms of their hunting and vocalising behaviours. The sperm whale and the pilot whale pictured here both have teeth, both eat fish, and both use echolocation.

Useful webpage on classification: https://iwc.int/about-whales/cetacea

Sperm whales are probably the Megafauna most associated strongly with Madeira through its history in whaling. They are a deep diver. Their call frequency range goes down to about 38hz.

Blue Whale

Baleen whales have even lower frequency hearing - down to about 16hz. The Blue Whale is probably the most famous of all whales since it is the largest. Blue whales migrate past Madeira once a year so they are known here, but not common. Humpback whales are also seen here and have a famously interesting ‘song’.

QUESTION: Which whale anatomy to focus on when designing a sculptural interface? I suspect the availability of scans will be the deciding factor.

“As low frequency sounds travel much farther than high frequencies before attenuating, baleen whales likely use low frequencies to communicate over long distances11,12,13.” Dziak, R. P., J. H. Haxel, T. K. Lau, S. Heimlich, J. Caplan-Auerbach, D. K. Mellinger, H. Matsumoto, and B. Mate. "A Pulsed-Air Model of Blue Whale B Call Vocalizations." Scientific Reports 7, no. 1 (2017/08/22 2017): 9122. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-09423-7. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-09423-7.

“Thanks to the oceans’ interconnectivity and acoustics, the same baleen whale sounds can propagate across the continents” Radeta, Marko, Nuno Nunes, Dinarte Vasconcelos, and Valentina Nisi. "Poseidon - Passive-Acoustic Ocean Sensor for Entertainment and Interactive Data-Gathering in Opportunistic Nautical-Activities." Paper presented at the Designing Interactive Systems, 2018.

idea six: 52 blue (after derek jarman and ‘the loneliest whale’)

Most of underwater observation all you see is water and the source or identity of sound is often ambiguous.

Photo Victoria Evans, Praia do Garajua, 28 October 2023

52 Blue is an unidentified individual of an undetermined species (most likely fin whale or blue whale with whom it shares a migration patterns) is known as the loneliest whale in the world because it calls at an unusual frequency of 52 herz, higher than normal. This is same frequency of G#1 (51.91Hz) the twelth note from bottom on the piano keyboard. In art and popular culture 52 Blue has been characterised as “The Loneliest Whale” *, and of “singing a song that no other whale can hear” although this would seem to be only a poetic conjecture since other whales can easily hear this frequency….

Visuals will be fifty-two different shots all of different shades of blue and aquamarine.

What would an underwater soundscape be to accompany the blue videos?

Human’s don’t locate sound very well in water due to the fact that sound travels five times faster. Cetacean heads are very broad so they have excellent positional hearing.

PROPOSAL: Build a binaural recording device five times wider than a human head in order to create a kind of whale version of ASMR. Something buoyant but weighted so that it floats below the surface.

NB: I’m not sure about whether this project would be ‘useful’ for the residency so for now I will pursue it in my own time, building up a library of materials at weekends for editing once I’m home.

*Zeman, Joshua. "The Loneliest Whale." 1’ 36”. USA: Bleecker Street Media (USA). https://www.imdb.com/title/tt2401814/?ref_=ttco_ov.

**Jarman, Derek. "Blue." 1hr 19’. UK: Channel Four Television Corporation, 1993.

IDEA EiGHT: coda coda; or, the whale and the blackbird

“In music, a coda is a passage that brings a piece (or a movement) to an end. It may be as simple as a few measures, or as complex as an entire section.” (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Coda_(music))

Whales give distinctive calls, known as coda that are thought to have a social function.

Humpback whales have been called the songbirds of the sea due to their complex calls. CHECK WHERE I READ THIS…

There is such a thing as a fish chorus. Is there a relationship to be made here between calls in air and calls in water? Some kind of bird/fish or whale duet?

waves

Other work this week was mainiy reading articles about how acoustic (and other) waves work and beginning to learn about the fundamentals of ocean acoustics.

Au, Whitlow. "The Sonar of Dolphins." Acoustics Australia 32, no. 2 (2004): 61-63.

Bradley, D.L., R.R. Stern, and United States. Marine Mammal Commission. Underwater Sound and the Marine Mammal Acoustic Environment: A Guide to Fundamental Principles. Marine Mammal Commission, 2008. https://books.google.pt/books?id=YCXhjgEACAAJ.