multi-perspectival perception in the forest: an art-geoscience collaboration.

Or, on following the noise when you can’t see the wood for the trees.

Diary notes on a research collaboration with geoscientists Richard Essery and Cecile B Menard. Supported by Ascus Art and Science, Edinburgh. This initial phase of research took place between November 2021 and May 2022. Plans for producing more resolved outcomes and for sharing findings in a public event are hopefully forthcoming.

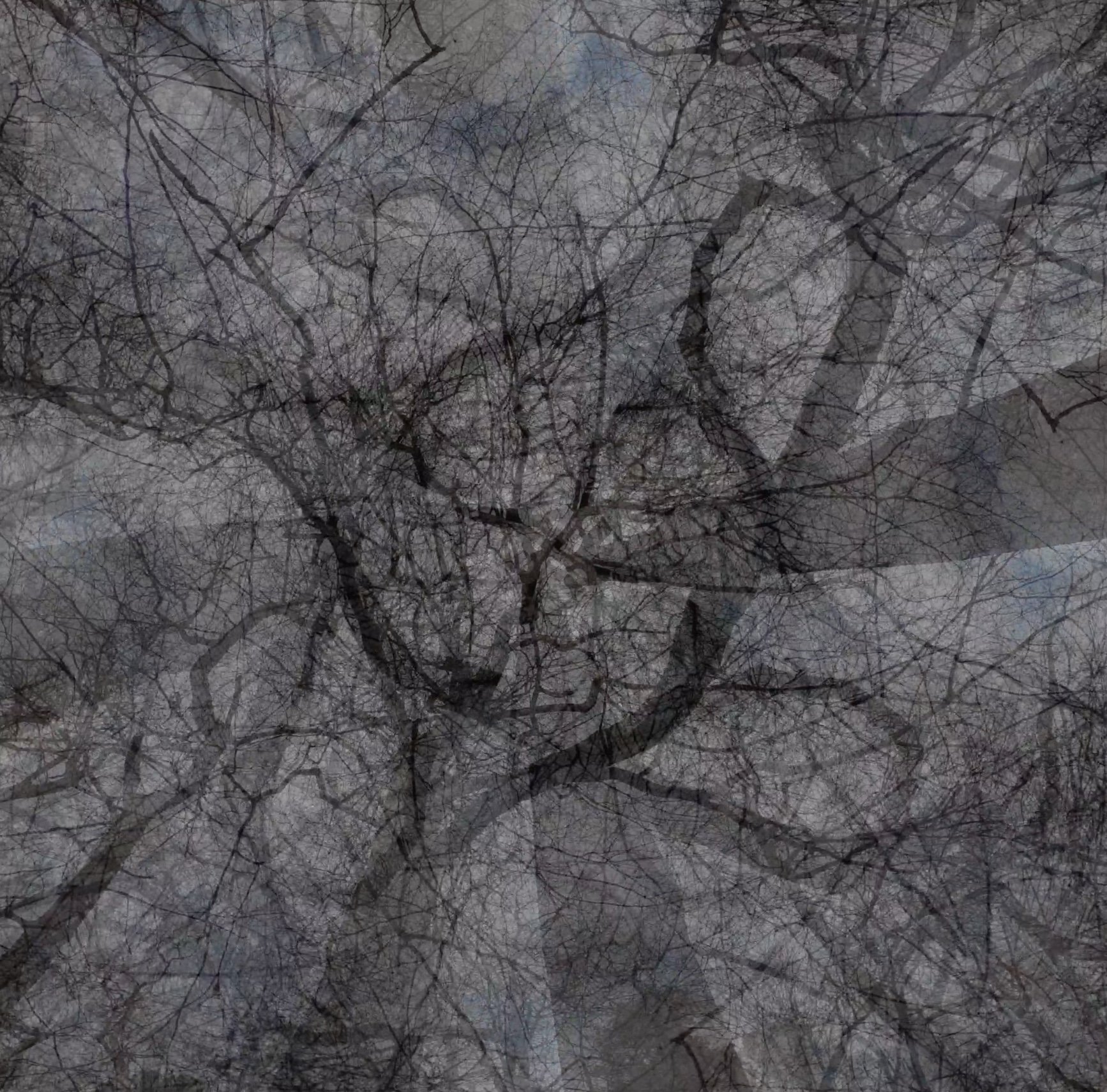

(Fig 1) video of layered multi-perspective POV of tree canopy x 2

METHOD:

Meetings and presentations

I was introduced to Dr Cecile B Menard and Professor Richard Essery by Miriam Walsh at Ascus Art and Science, an Edinburgh based arts organisation who presented my installation Oscillations at Summerhall Gallery for the Edinburgh Science Festival in 2021. Ascus specialise in facilitating art-science connections. Cecile Menard works across the School of Geosciences and the Institute for Academic Development at the University of Edinburgh and her research looks at how research cultures and environments affect research practice. Richard Essery specialises in cryosphere-atmosphere interactions: for example the ways in which snow on land and sea ice reflect a lot of solar radiation, keeping the surface cool.

This is a process of getting to know one another and what we hope for from the collaboration. Cecile wants to interrogate the perceived demarcations between who is creative and who is not in artistic and scientific fields, and Richard has an interest in communicating his work visually/artistically. I am always interested to talk to scientists, to explore the relationship between representation and experience, and to discuss epistemic beliefs and practices. We quickly agree that there can huge creativity and inventiveness in scientific enquiry. and some of Richard’s visual methods are stunning - readable as art projects to my eyes.

We discover some shared fascinations: measurement; how models relate to ‘reality’; I am struck by the infinitely contestable term ‘ground truth’ that the geoscientists use - meaning on the ground measurements that are necessary for calibrating remote observations and improving models. This is a productive idea for me - my practice is concerned with the tensions between, and entanglement of, the abstract and conceptual with felt, lived experience. There is an exciting moment, quickly qualified, when Richard states that models can be ‘more real than reality”. What he means is that, when models are all we have, eg. in cases where ‘ground truth’ is not verifiable - on an inaccessible mountain peak for example, they are our best means of ‘observation’. We discuss how even where it is accessible, direct human perception is also intimately tied up with context and best guesses. Seeing with ones own eyes is not what it’s cracked up to be.

My research often positions sound and listening as an alternative way of “seeing”, so a nice resonance sounds when Cecile talks of the scientific images she collected but couldn’t use because they were contaminated by “noise”. This noise is in the form of a mosquito landing on the hemispherical lens used to collect information about light penetration in the forest. What a scientist may need to exclude, an artist may choose to amplify.

Cecile stresses that speculative work can be useful in science as a starting point in order to try out hypotheses or make a test case for what might work with more precision later. “If you are at the start of a hypothesis, then you can get a lot out of something that isn’t necessarily super accurate. Some information is better than nothing” Cecile B Menard

I am keen to experience the scientist’s work first hand. I ask to look round their office - naively imagining it will be like a lab or artist’s studio - offering immediate clues as to the practice enacted there, but Richard explains I will mainly just see desks with computers. We decide to conduct a field trip together. There is one of Richard and Cecile’s projects that has piqued my interest and in practical terms is easy for us to undertake in a day. It involves methods for measuring tree density as a way to quantify how fluctuations in ground temperature affect snow melt.

Interim: Trains of thought & flights of fancy

Temperature

Measurement

The multi-subjective - rigour without singular objectivity

Tree density

Data as image

Insect or human as noise in the data

Follow the noise

Mosquito

Mosquitos fly by sculling, using fluid dynamics to swim through air.

They see through compound eyes with hexagonal lenses

Geology as a way of compressing time.

The new James Webb space telescope array. looks for infrared light from the early universe. It uses eight hexagonal mirrors to form a compound perspective of one point in space.

Ways of seeing.

Sub-headline in New Scientist "For the first time it is possible to see the quantum world from multiple perspectives at once. This hints at something very strange - that reality only takes shape when we interact with each other.”*

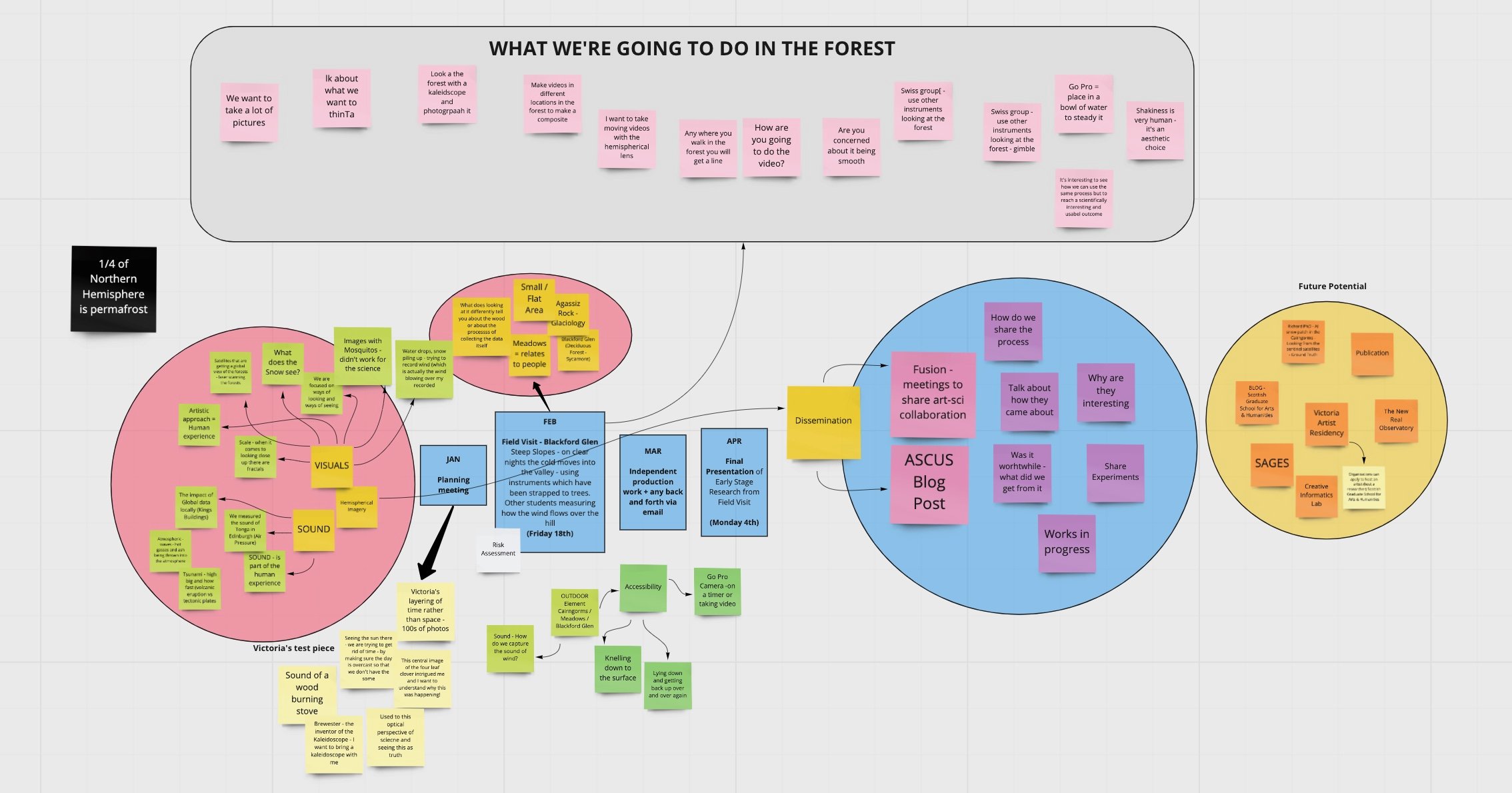

(fig 2) A Miro whiteboard put together by Miriam Walsh at Ascus with stickers enabling us to share ideas and plans online outwith meetings

Field trip - Blackford Glen

Anecdotes:

We pass the University weather station on the way to the Glen. Richard mentions that in his work it’s important to have access to multiple readings. “The easiest thing to do when evaluating models is to take the perspective of a single point, but this is not very meaningful.” Richard Essery. There might be two weather stations only 20 m apart which give vastly different readings, if there was one, Richard explains, we’d think we knew what was there, but because there are two, at least we know we don’t know. We joke about Donald Rumsfeld and known unknowns.

We pass a seemingly unremarkable spot which has huge significance in geological science. It is called Agassiz rock and the story Richard tells behind it is explosively apophenic for me. Louis Agassiz a naturalist from Switzerland who came to Scotland in 1840. He noticed that the striations on the rock surface were similar to those that could be seen in Switzerland and were known to be the result of glaciation. Up to that point it was not thought that glaciers had covered Scotland during the ice age but now we take this idea for granted. For me this story resonates wildly with questions of how knowledge is produced and comes to be taken as common sense; as well as giving an example of how the immensity of geological time scales can collapse when we experience material-conceptual traces such as these. I’m already enthused and we haven’t even reached our destination.

Richard wants to know how much sunlight a certain spot in the valley is exposed to. He measures the tree line from the position where a temperature reading has been taken. He uses a type of sextant called an Abney scale and Cecile notes down the 360 degrees of measurements, making a guessing game out of what the next result will be. I feel like I’m on an old fashioned expedition. I’m imagining that we may run out of lemons and have to eat tortoises at any moment (according to Darwin they are delicious). We are still on the outskirts of Edinburgh, but I’m a city girl.

Richard lets me have a go of the Abney scale and I ask how he’s choosing where to define the end of the tree-line since it’s a fuzzy line and not obvious to me where the sky ends and the trees begin. He says it’s a good question and we banter again about subjectivity and whether there is any such thing as objectivity. This is a theme I return to with (possibly annoying) regularity in all our discussions since it’s an artistic preoccupation of mine., and although our perspectives differ - at least in terms of our research aims, we understand each other more easily than I had expected. In the end though, Richard is here to do science and concludes that he is not satisfied with its accuracy of the sextant for measuring in forest conditions. It’s something he normally uses in more barren mountainous areas. Instead he much prefers the data he has recorded visually using the hemispherical lens (fig 3). Later, he adds a yellow line to black and white version of the image (fig 4), signifying the arc of the sun’s movement on that day. I imagine it will be easy to compare throughout the year as the cycles of sun’s arc and leaf cover changes the light penetration. Richard will use these images to produce quantitative data, but to me, they are graphically pleasing in themselves. Repeatability is a requirement of the scientific method, but iteration and repetition interests me artistically too. I could imagine an intriguing installation stemming from multiples of these functional images and this is something that Richard already produces in the course of his work.

(fig 3, left) Hemispherical image from spot Richard measured with Abney scale, featuring human “noise” (me in a bobble hat) photo Richard Essery

(fig 4, right) Black and white version where pixel count will enable quantification of light penetration, together with line of solar passage (in yellow) photo Richard Essery

My Experiments:

Take a home-made three mirrored triangular kaleidoscope into the forest to produce an analogue multiple image from a single spatio-temporal perspective. Use this as a lens adaptor to produce a compound video image.

Take footage on a wide angle setting on GoPro, looking upwards into the tree canopy, aping Richard’s use of the hemispherical camera to gather horizon tree density data.

Document the documenter, Miriam, accompanying us as with her camera since. As any quantum physicist, anthropologist or documentary film-maker will tell you, the act of being observed alters what is being observed. But who is the watched and who is the watcher? (fig 5 & 6)

(Fig 5, left) Victoria Evans using home made kaleidoscope over go-pro camera to photograph Miriam Walsh (photo Miriam Walsh)

(fig 6, right) Miriam Walsh documenting the field trip seen through the kaleidoscope camera (photo Victoria Evans)

Initial outcomes - ideas for future development: Enforested perception

I collaged four of the upward POV tree videos, rotated each by 90 degrees to produce a composite moving image. This worked best when a single video was seen from multiple angles - leading to the emergence of a kind of flower pattern at the centre, reminiscent of the interlacing designs found in Celtic and Islamic art. These are often interpreted as relating to infinitude, the eternal, or - as I might prefer to put it - the inseparable and the continuous.. I tried out four-layered and six-layered configurations . I discovered that when the wind blows, the pattern created centrally shifts and changes as though the lens on a kaleidoscope is being turned (fig 1). For a future presentation of this work, I plan to combine multiple versions of this compound video images, from footage taken from different spots, either in one, or across several woodlands or forests in Scotland. These moving images will be cropped and combined so as to tessellate in a hexagonal array of 16, alluding obliquely to the compound eyes of insects like the mosquito (the “noise” in the observation) but also to the new technologies for extreme observation such as exemplified by the James Webb telescope. The images will be combined with a soundtrack based on field recording with contact microphones, as a way to access the interoceptive sound world of the tree. The resolved work will, I hope, provide a meditative and speculative experience of the forest; a way to experience a shift in perception perhaps. One that might open up the concept of forest as a simultaneous multiplicity, open to more-than-human sensorial experiences. A study in enforested perception.

*GAFTER, A. 2022. Do we create space-time? A new perspective on the fabric of reality. The New Scientist. London: The New Scientist.